While some have commented that the impacts of COVID-19 are felt across society, that the virus disregards social class, gender, and ethnicity, it is clear that this misses a crucial point of how the virus impacts the most vulnerable in our society. COVID-19 has not only highlighted the pre-existing inequalities within our society but has also caused them to become further entrenched. Recent data released by the ONS (whilst pertaining only to England and Wales) shows that COVID-19 deaths are 118% higher in the most deprived areas as compared to the least deprived areas. Inverclyde which is one of the most deprived areas in Scotland has seen the highest mortality rate from COVID-19 across Scotland. A national critical care audit across the UK showed that despite making up only 18% of the general population, people from BAME groups represent around 32% of critical care patients, the reasons behind this are far from pathological but are indicative of underlying social and economic inequalities.

A recent survey carried out by VHS of our member organisations and our regular engagement with the voluntary health sector has shone a light on these inequities and the impact of the social distancing measures on people’s health and wellbeing. We are hearing of the impact on people’s mental health with an increase in fear and anxiety in those with existing mental health conditions but also increasing poor mental health for people who are normally emotionally resilient.

What we are finding with COVID-19 and the current situation with social distancing and isolation measures is that loneliness and social isolation is becoming more widespread and those who are already marginalised are now worse off. The loss in social contact is exacerbating poor mental health. People with strong social capital are now feeling isolated and this is worse for those who already lack social connections – as they are often further away from accessing both formal and informal support and networks.

This is only made worse by issues such as digital exclusion whereby people do not have access to digital technology or access to the internet, mobile phones, or phone credit.

Many people are experiencing a loss of income due to self-isolation, job losses and business closures. People are noting difficulty in accessing benefits which is further impacting on their mental health and wellbeing. Recent research conducted by the Work and Pensions Committee shows that 75% of the people they surveyed do not think Universal Credit covers their basic living costs such as rent, food, internet and utilities.

People on low incomes or gig economy workers – who can’t choose to stay home if their employer won’t furlough them – are being forced to choose between earning a living and compromising their health. In work poverty is a massive issue in Scotland, where 53% of those in relative poverty live in households where at least one adult is in paid employment.

The issue of food poverty or insecurity is being further compounded by a lack of access to food and issues with food distribution. New data from the Food Foundation shows that more than five million people across the UK who live in households with children under 18 have experienced food insecurity after a month of lockdown.

We are also hearing about an increase in alcohol, tobacco and drugs use as a coping mechanism during the lockdown. A number of organisations have also told us about an increase in people reporting suicidal thoughts.

We must recognise that this is all happening in a backdrop of a decrease in face-to-face services and as NHS staff are redeployed to help with COVID-19, there is a fall in what is deemed non-essential healthcare. This is all adding to the stress and anxiety of those with existing conditions, those self-managing conditions and those who have recently been diagnosed. All of which will have long term implications on people’s general health and wellbeing but also on the demand for services and support post COVID-19.

The voluntary health sector and wider civil society are part of the public health workforce and are well placed to help and have been rapidly adapting to reconfigure and extend their services. Indeed, we have noted the enormous amount of creativity, adaptability and swift action on the part of the voluntary sector in dealing with the crisis. Many organisations have adapted and extended their services and are now providing a suite of online, telephone based and some face-to-face services. Some organisations have even used their own funds in order to buy people equipment such as tablet’s and phones so that they can stay connected and access support.

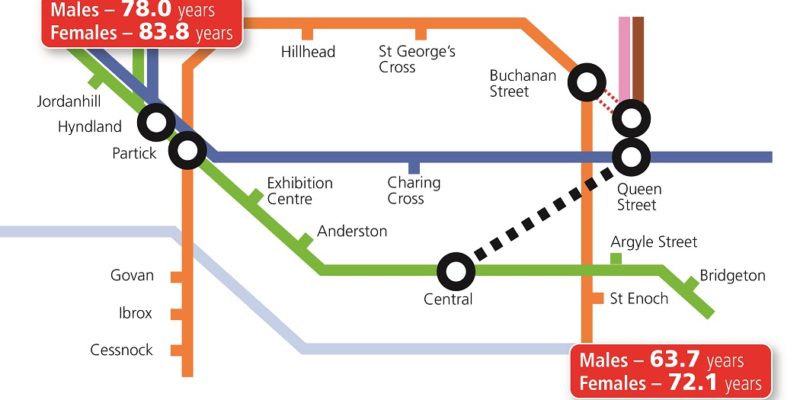

However, there is a need for this to be sustainable and for this community level momentum to be maintained post COVID-19. This needs to be supported by appropriate national and local government policy and actions that are informed by those that are affected. We know the gap in life expectancy between those from higher and lower income households has widened over the last decade and this is being increasingly linked to the post financial crisis austerity measures – the social and economic impact of COVID-19 could be much worse. It is therefore imperative that all future policies, strategies and legislation are centred around protecting the health, wellbeing and inclusivity of those who are most vulnerable in our society.

What is becoming increasingly apparent is that the implications of COVID-19 on people’s health and wellbeing will transcend the duration of this pandemic. It is imperative that there is continued assistance and services available to communities and especially to those who are most vulnerable, in order to provide people with a buffer from the long-term consequences of COVID-19.

What is positive is that the conversation is moving towards building back society to be better, more inclusive and equal. As a society we are seeing more open and visible debate on issues such as Universal Basic Income, the importance of wellbeing as a measure of national success and co-designed and inclusive policy development. A report commissioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation into public attitudes in Scotland pre-pandemic showed large scale support for bolstering the welfare system. Even during the pandemic, we are seeing a growing civil society with increased volunteering and active engagement at a grassroots level to support those who are most vulnerable. It is important that these conversations and ideas are given space and momentum to change the course of our inequalities trajectory.

For further information please contact: Kiren Zubairi, Kiren.Zubairi@vhscotland.org.uk