This blog by Emilie McSwiggan, a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, outlines findings from a review that aimed to summarise what questions have been addressed in social prescribing research so far.

Social Prescribing research is booming

Research and policy interest in social prescribing has started to grow at quite a pace in the last few years. It took twelve years for the first 100 academic papers on social prescribing to be published. But since 2022, more than 100 papers have been published each year – and that number is only going up.

To put this in context, this is still very small compared to most health-related research topics. But it shows that people are really thinking about social prescribing and trying to produce good evidence to make it as useful as it can be.

In addition, as published research studies increase, so do ‘literature reviews’ – academic papers which try to summarise all the research that’s been done on a particular aspect of social prescribing (or any other topic). These reviews are often done in preparation for new research, or in answer to decision-makers’ questions. So they’re really useful for indicating what topics are most important to the people doing, funding and using social prescribing research.

As I prepared for my PhD research on social prescribing (which you can find out more about here), I worked with my supervisors to try and find, analyse and summarise all the literature reviews which have already been published on social prescribing. I wanted to know how many of them dealt with my particular topic – but I also looked at their general characteristics: what kind of health or social needs were they concerned with? What models of social prescribing did they use?

Since I’ve started getting to know people who work in social prescribing in Scotland, I’ve realised how much enthusiasm and support there is for good-quality research and evidence within the sector, and how many of you rely on this evidence to help with planning, designing or evaluating your own services. I wanted to share our work in the hope of saving you some time – so you can use our work to quickly find evidence that’s relevant to your interests, or easily spot gaps where we may be missing important research.

Here’s what we found out

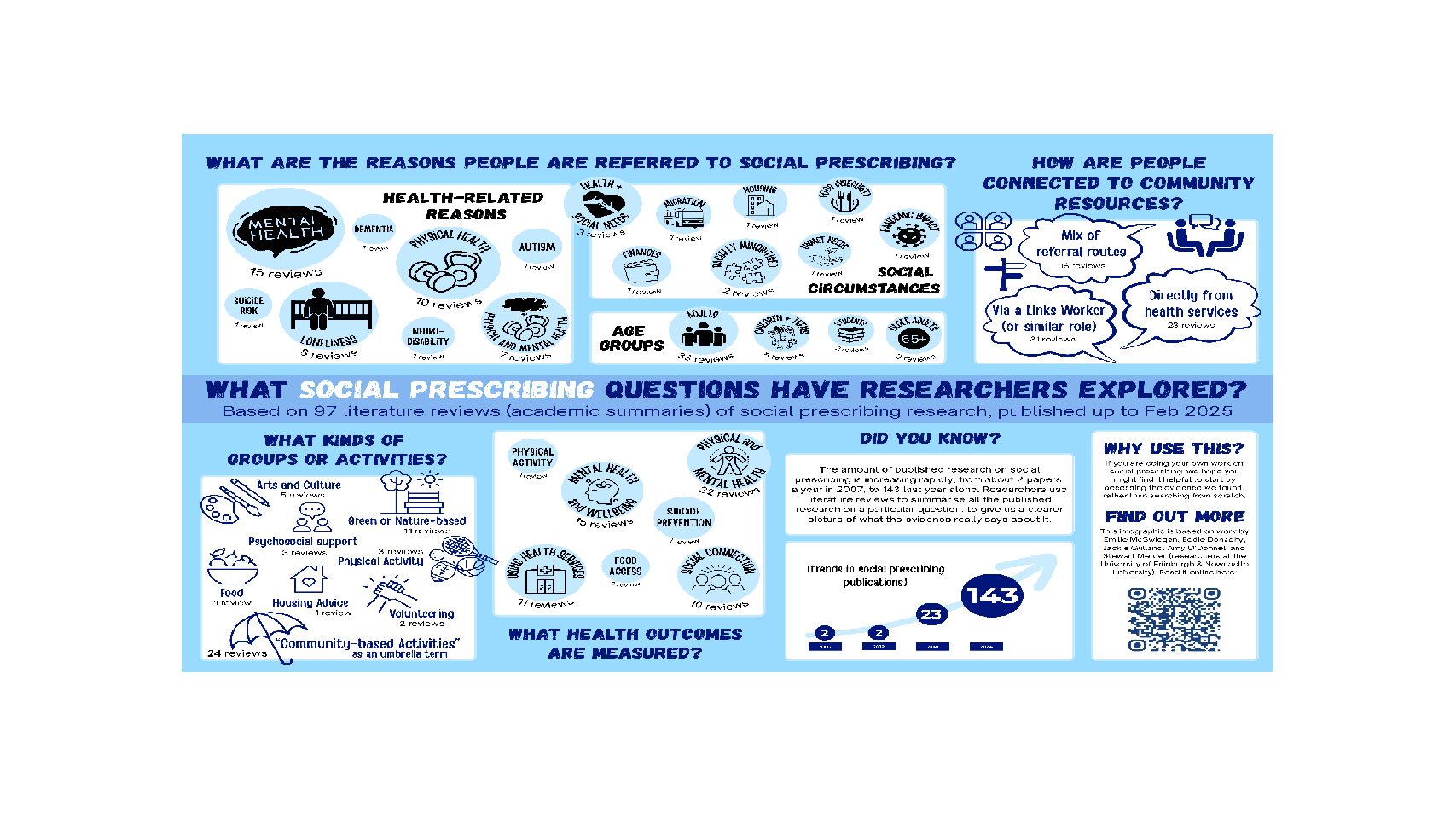

The infographic above summarises what we found and you can access a higher resolution version of it via this link. I’ve also described it in writing below, and suggested why it might be helpful to know these things. If you want to follow up on any of this, you can access our paper (online, free of charge) here. The paper has details of all the reviews that we included, under each of the headings mentioned in the infographic, so you can get straight to the research that interests you most.

Why are people referred to social prescribing?

This information might be useful if you are designing a social prescribing programme for a group of people who share a particular health need or social situation.

We found 15 reviews relating to people with mental health needs, 10 on physical health (particularly chronic conditions), and 7 for a combination of physical and mental health. In 8 reviews, people were referred because of loneliness, and there was one review each on autism, neurodivergence or neurodisability, dementia, and suicide risk.

Three reviews combined physical or mental health needs and social circumstances. Eight reviews focused on a particular social circumstance – finances, migration, housing, food insecurity, unmet social needs, pandemic-related conditions, and experiences of being racially minoritised.

What social prescribing models and interventions are used?

This information might be useful if you are thinking about how to structure a social prescribing programme, or what community organisations might fit well with your aims.

We found 31 reviews which exclusively used link-worker models of social prescribing. In another 16 reviews, link worker models were included alongside other types of community referral (such as directly from a doctor or nurse).

Reviews focused on a range of different types of project or activity, including: green- or nature-based opportunities (11 reviews), arts and culture (5), physical activity (3), psychosocial support (3), volunteering (2) and one each on food and housing. Another 24 reviews referred to ‘community-based activities’ in general – this is a big umbrella, which could also include lots of these different types of activity.

Was social prescribing intended to achieve a particular (health or wellbeing) outcome?

This might be useful if you are thinking about what is realistic for a social prescribing programme to achieve, in terms of its benefits for the people who use it.

We found 32 reviews which measured general health and wellbeing outcomes, meaning physical and mental health – 10 of these also looked at how much people used other health services (and one looked only at this). 15 reviews measured mental health outcomes, and 10 looked at outcomes related to loneliness or social connection. Outcomes such as physical activity, suicide prevention and food access were the focus of one review each; and one review measured a combination of personal and systemic outcomes.

A few words of caution

We wrote the paper that this blog is based on in February 2025, and lots more social prescribing research has been published since then, although hopefully it’s still a useful baseline. I have produced a spreadsheet, with details of all the reviews summarised here, which I am also happy to share – if you are interested in one of these headline statistics, this might be the quickest way of finding evidence that relates to it.

There are different ways of doing literature reviews, some of which lead to more confident findings than others. We haven’t distinguished between strong and weak literature reviews in this piece of work, but this can be important to understand if you are using these as the basis for your own plans.

I worked together with my PhD supervisors on this research – Stewart Mercer, Eddie Donaghy, Jackie Gulland and Amy O’Donnell. I also had valuable input from Paul Kelly and Kevin Chalmers, my lived experience advisers. Any errors that have snuck in to this blog or infographic are entirely my own! Please get in touch with Emilie if you have any questions.

Emilie McSwiggan is a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh